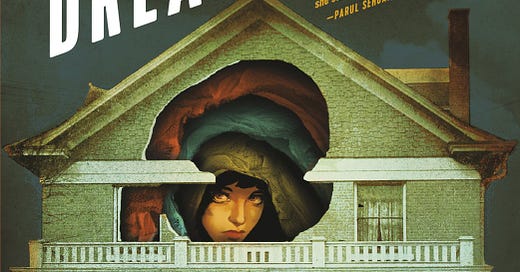

Dream House as Silence in The Archives.

A review of In The Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado.

I am listening to - a recent development in my reading habits, I feel I can do more when I listen - In The Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado when I realise that I know nothing of myself. In the book, the writer is examining her relationship with a “charismatic and volatile” woman. She brings to mind the events of this relationship, but the prologue - a narrative method she does not favour - is what I ultimately carried along with me through her story.

Machado delves into this with a focus on the history of queer abuse, how its lack of documentation has made it an anomaly. I, myself, don’t know much about the history of queer abuse, specifically abuse within lesbian relationships. There are plenty of traumatic films about gay men in abusive and toxic relationships in perhaps every language, but seldom about women. Maybe I’m not looking, or maybe we’re not taking note.

Even after finishing the book, I’m still not sure if the Dream House was meant to be a physical location or space she was in during the relationship. If I were to guess, The Dream House is isolation, is flesh disguised as brick, and is transient. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter to me, because the book has still cemented itself somewhere deep within me. I liked Machado’s writing, and her long and indirect way of storytelling. I was taking notes, honestly. To be able to plant your words into someone else’s hands for them to interpret is not easy work. Even now, I still fear that my parents will find out that I’ve been writing about them.

This is what terrifies me about writing a memoir or something adjacent. You are not making things up, and despite the creative liberties you might take with a piece of written work, you are still trying to decipher and record real feelings. Real people.

I excel at making things up. Living with strict African parents has turned me into quite the liar. In the book, Machado notes that “fear makes liars of us all.” In fear of what I might do to the relationship I have with reality, I turn to fiction. I guess you could say that all fiction is a lie but that would be reductive. Anyhow, I am good at making things up. So if you tell me to write about my life, the things I have been through, I don’t think I could do it.

I must disclaim that writing about your real life is very different to writing what you know, even if what you know is your life.

The novel I am currently writing takes place in a world I am vastly unfamiliar with; London, 1986. I am researching like a dog because I don’t want to get things wrong, and even if I do, I want to be as close as I can be to the truth. This doesn’t mean that I will be writing about real people, but I will be writing what I know. Love, heartbreak, displacement, mortality, morality, Trying your very best to be the best for the people around you. Even now, as you’re reading this, you can feel one of these deep in your bones, calling you towards a memory you cherish, or perhaps resent.

In all of these things, there is a personal archive you create that builds the foundation of your person. In recent times, it is more common to see a piece of your archive within someone else. We build and grow communities by pouring into one another. In other situations, some archives are lost to us. In a Guardian review for Jason Okundaye’s debut book, Revolutionary Acts, Lanre Baker praises the book for recording the lives of some of Britain’s first Black men out in society. It brings to life “these stories that have long been obscured.”

Black archives, like today, exist within bodies. Parents, grandparents, friends, communities. You find your history within these people when it’s not made available to you. Everything I know of myself I’ve learnt from my parents, my siblings, aunts and uncles.

“Why did no one tell me? But who would’ve told me? I knew so few queer people and most of them were my age, still figuring this out themselves. I imagine that one day, I will invite young queers over for tea and cheese platters and advice and I will be able to tell them, you can be hurt by people who look just like you.” - In The Dream House - Carmen Maria Machado

In the book, however, Machado mentions that there are things you simply can’t archive.

TW: mentions of physical abuse

“You’ll wish she hit you. Hit you hard enough that you’d have bruised in grotesque and obvious ways. Hard enough that you took photos hard enough that you went to the cops. Hard enough that you could’ve gotten the restraining order you wanted. Hard enough that the common sense that evaded you for the entirety of your time in The Dream House had been knocked into you.” - In The Dream House - Carmen Maria Machado

She admits that this ‘fucked up’ fantasy was unfortunately the solid proof that wasn’t accepted as such. The countless cases of women destroyed by abused partners were dismissed all because she didn’t bruise. I sometimes wonder if a victim has to die to be taken seriously. To be considered as a case left too soon, or the stepping stone for saving future victims because there will always be future victims.

These are the kinds of things that the body archives instead of the court. Machado takes note of it, that this kind of temporary evidence doesn’t work in a court of law, “Because there are many things that happen to us that are beyond the purview of even a perfectly executed legal system.”

I think the narrative style of this memoir puts us in a place where we can understand what she’s feeling, even if we haven’t been in an abusive relationship. She explains the brutal and perverse manner in which she’s treated with what someone on Goodreads described as ‘too much purple prose.’ I can see that, however, I can also see that Machado is writing from a different mind, a different body. She writes in a second-person narrative and addresses her abuser as ‘The Woman in The Dream House’ It is direct and all the while removed. We can understand the feeling of watching someone you love hurt you and empathise with the writer in moments we don’t understand. A memoir like this doesn’t expose itself to you as simply a memoir, it exists, quite like the transient, and sticks to you when you least expect it. It becomes your own personal Dream House.

Ugh such a beautiful review Ennie! Loved the line "The Dream House is isolation, is flesh disguised as brick, and is transient."

In The Dream House was definitely one of my favorite reads of last year.