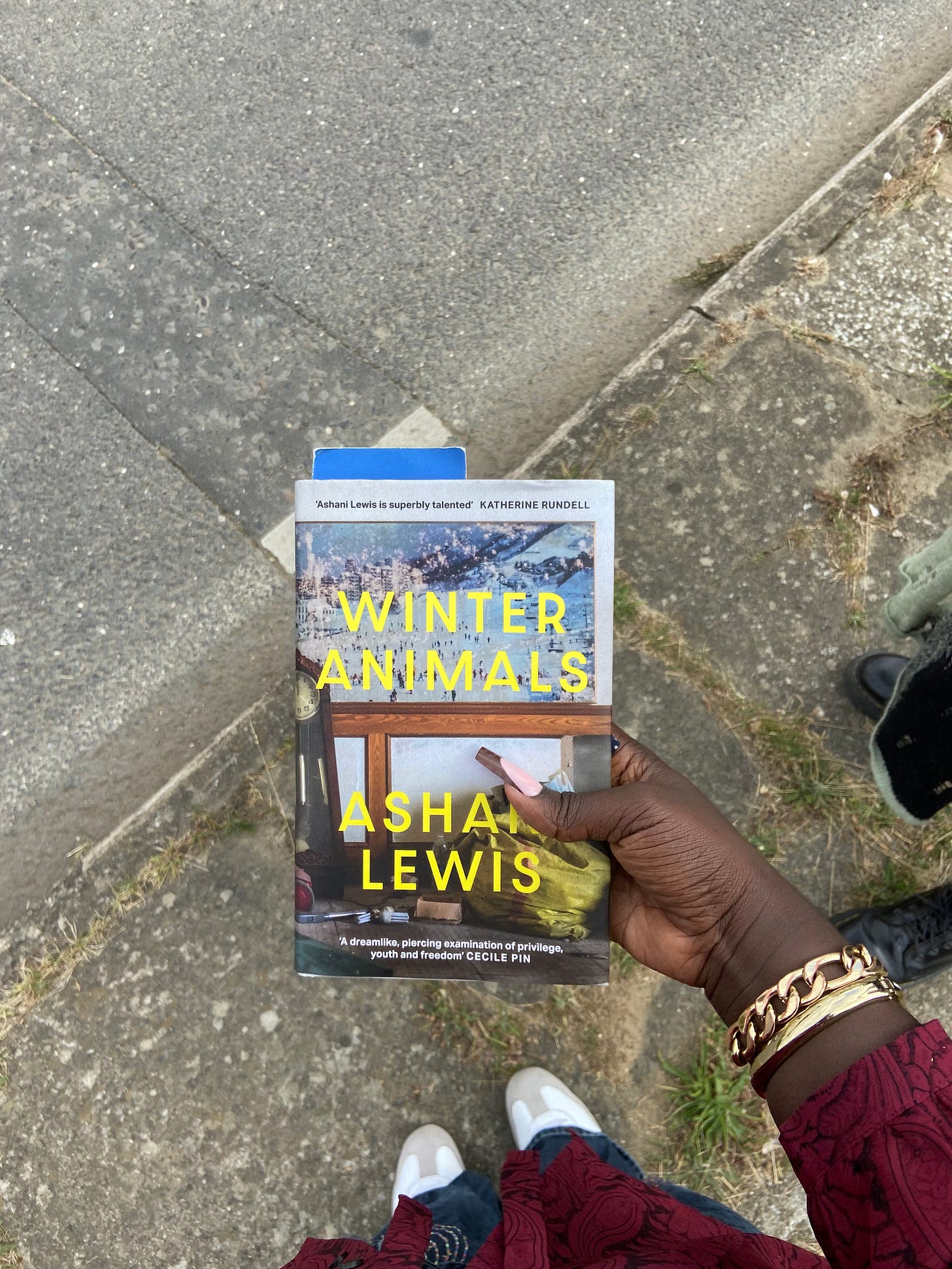

Word vomit: Winter Animals by Ashani Lewis.

Cultish foreigners, French Socialists, and too much skiing.

Trigger warning; spoilers, descriptions of death.

I find myself reading more about cultish exploration these days. In this particular instance, these explorations are found in Winter Animals by Ashani Lewis.

Usually, and especially in the case of literary fiction, I feel a sense of loss or gain after reading. Knowledge, wisdom, a second lens to an experience I would’ve never come across if not for the words that I read. My current read is Our Wives Under The Sea. One of the main characters is a deep sea researcher, whose pov we get every other page talking about the ‘incident’ but also the facts surrounding the incident. The zone they’ve fallen into based on feet metrics, the inhabitants of the deep sea, etc. etc. In a way I don’t care about the deep sea but I’ve come to care about Leah, who, in present day, is seen through the eyes of Miri, her wife. The knowledge and the facts have a stake on the lives of the characters, which is something I can’t say happens in Winter Animals.

To be completely honest with you, I’m still not sure what happens. We end the book how we started; With no idea of who the characters really are outside of the superficiality already established. A quick summary; Elen, in her late thirties has been abandoned by her husband. She’s distraught (thought the feelings she tells us in conjunction to this are disorganised) and on a random day in an empty bar, she is approached by ‘four English teenagers’ who essentially accost her into their squatting utopia(I use this word loosely).

The two main locations are an abandoned ski resort and an Airbnb they break into. The setting is ultimately what’s focused on most prominently in this book; lush descriptions of rocky mountains and cascading snow. It’s all very beautiful. I just thought it would inform the plot a lot more.

In being truthful, I’m going to admit that anytime I read books like this, books that offer themselves up as ‘vibrant and cultish’ I think of murder. I think about disturbing acts of debauchery, I think of a certain contemplation of what it means to be human in such a setting. I don’t know much about cults but when something is described as ‘cultish’ I tune in because I have a gnawing sense of curiosity that’s usually enough of a push to get me through. I also enjoy the focus on a character outside or somewhat removed from the rest of the cult, and I think it makes for excellent character driven stories.

PART ONE: The protagonist is not a good protagonist.

Elen is perhaps the biggest culprit of the lack of movement in this book. She’s a decade and some older than these teenagers—who she also describes as being older than University age?? So??—so she ruminates often on the said gap and their idealistic pursuits of a youthful utopia. We’ve seen this story before, so I was clearly excited for the character study and the conflict that would clearly arise with this middle aged woman living with 20-year-olds for however long she lived with them.

This doesn’t happen. Her husband’s brother and sister-in-law call her regularly by the time she’s moved into the haunted resort with the squatters but she responds to neither of them. There is no instance in which she’s caught out, no instance where she’s questioned about why she’s still with these kids, which might have been the aim of the author but for me it fell flat.

Elen is also a product of her environment. Certain books start off with the protagonist getting approached, and the protagonist being given a map of their journey, and a protagonist being given a wise guide. I’ve realised in recent years that I have no interest in characters that aren’t in control of their actions. Not all the time, obviously, but Elen is approached by the squatters, she’s taken to the resort where they ski and ski and ski again. She thinks about seeing her parents in Michigan but then everyone quietly presumes that she’ll be following the squatters to their next destination and so shall it be. When they’re at the airbnb, she sees ghosts in bottles and creepy doors and that’s it. Nothing comes of Elen’s minute attempts at gaining control of the situation, and in fact i don’t think she actually tries to. Perhaps it was intentional to strip her of her control, to place her in a situation with these rich foreigners with more means and resources to leave her behind or trap her. It definitely has the markers of a cult, however I simply don’t see it. Elen agrees almost immediately to stay with the squatters—who I’ll remind you, around 20-22 years of age—and when one of them, Luka, starts tweaking about about another, George, disappearing, it isn’t treated so much as it problem as it is a blip in their plans. I’d expected her to be a separate voice from them, an ‘other’ in the sense that we’d see the squatters through this rose tinted lens and then we’d see how Elen managed to detach and escape. No suck luck.

PART TWO: Who’s afraid of French Socialists?

The leader, Luka, is very much a Henry Winter in his own right, although his presence more resembles Bunny; charismatic, charming, sweet faced. All the pretty things about youth and desire are shoved into his character and for the most part it worked for me. Luka has a stiffy for Charles Fourier, an 18th century French philosopher and socialist. He very much adopts Fourier’s recipes for a successful commune and tries very hard to keep the nonexistent peace that only serves to make him look insane.

Towards the end of the book, Elen goes through Luka’s copy of The Utopian Visions of Charles Fourier: Selected Texts On Work, Love, Passion, and Attraction. There’s talk about sexual desire feeding social change, how the institution of marriage fosters universal deception and sexual dishonesty.

The most applicable part of the book to the current narrative was this: “The term group is conventionally applied to any sort of gathering, even to a band of idlers who come together out of boredom with no passion or purpose — even to an assemblage of empty minded individuals who are busy killing time and waiting for something to happen.”

In many ways it’s is an apt descriptor for Both I, the reader and Elen, the character, and how we’ve come to digest the lives and attitudes surrounding these squatters. The main similarity is the intrigue of alienage. Elen has practically nothing in common with these people, and it’s written like that so we can insert ourselves into Elen’s place. I was waiting for the reason behind their sudden comradery and yet no answer was given. But Elen had no problem with being kept in the dark. She had moments of opposition but it was all internal, and after a short while she would go back to killing time by drinking and skiing. She is positioned as though waiting for something to happen to her, and so I waited alongside, hoping that something more substantial held this story together because there literally was nothing else going on.

Their ‘phalanstery’ was in its teething phase but despite this they had money and resources to be squatters. Evidently, they’re rich. This fascinates Elen, and it fascinates me too, because I love seeing rich people humanised in the way you’d enjoy seeing a narcissist humbled. The secret history was a good book in my opinion because as much as I felt for them and their constant attempts to hide their crimes, I was also very aware of their positions as well off students in very privileged positions. They were all incredibly rich, and the ending only solidified the madness and delusion of young rich people when Henry kills himself for the sake of being seen as a tragic hero.

All of these people believe themselves to be something they’re not and in these cases it’s tied to their youth and a warped belief that said youth makes you invincible. There was a serious lack of self actualisation and I actually liked that. In TSH the students are forced to reckon with the fact that they can’t just kill people and have that be the end of it, but in Winter Animals I can’t say the same. There is no consequence for squatting and the implications presented with rich white kids taking breaking into places, no consequences for one of the squatters just leaving—and in doing so abandoning his situationship with this now pregnant girl. I really do wonder why they brought Elen into the fold. She wonders this too but obviously she doesn’t do much about it so I will.

With my original assumption that death might be a main plot point, I thought Elen was going to be a scape goat. No murder happened, and Elen was not the scape goat for anything. Prediction two was that Luka would’ve wanted a witness to their elusive little squatting cult. In line with the idea of a murder taking place, this prediction required murder to be more purposeful, more sacrificial. The squatting group get a chapter all on their own about their individual pasts, and later on we find out that Luka’s brother killed his friend with a katana. It was meant to be a challenge involving watermelons, which becomes a recurring point of tension because George keeps bringing it up.

I assumed that this was going to culminate in Luka going of the rails and also killing his friend, but with more of an intent to humiliate. He seems the type.

In a conclusion as abrupt as the one in the book, I do believe that the writing was gorgeous and Ashani Lewis has a beautiful way with words, but the words should have been shorter. If this were a short story centred on a singular moment in the middle of the story, I think it would’ve drawn more impact but alas, that was not the case.